Between 1959 and 1962 I was studying for a Ph.D. in Chemistry at Exeter University, but spent much of my time on a different activity - exploring the limestone caves in Devon. I became Secretary of the

Devon Spelaeological Society and was involved in the purchase and early work on an important geological and biological site - Higher Kiln Quarry, Buckfastleigh. However my grant ran out in September 1962 and as I needed an income I took a job in Hertfordshire. This meant that I just missed out on the creation of the

William Pengelly Cave Studies Trust.

A week ago the Trust reopened a refurbished museum and held their 50th AGM - so I decided to take a holiday revisiting Devon and get to know more about what had happened.over the last 50 years. So I went to Buckfastleigh to attend the reopening of the museum - and to enjoy a celebration meal at the Cott Inn, Dartington, after their annual general meeting. I was also interested to see some old films showing what had happened in the last 50 years.

|

| The Trust celebrate with a meal |

However the contact with the Trust reminded me of some unfinished work from the 1960's. While I was supposed to be studying chemistry I actually made some detailed notes relating to the formation of caves, particularly in the Buckfastleigh area. However the work was never finished as I was to busy earning a living and raising a family. As a result the bulk of my observations were never published.

There was one notable exception. In about 1960 I visited a cave in

Cheddar Gorge, Somerset, which was being explored by the

Mendip Caving Group, and wrote up an account of the deposits there. I was contacted for more details by an archaeologist in the mid 1990's and, based mainly on my observation, a

Time Team programme was broadcast in 1999. As a result I tidied up my original notes, did a literature search on later developments and published a detailed paper,

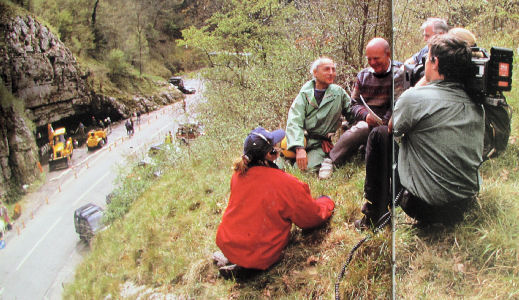

Cooper's Hole and the Cheddar Master Cave, in the Pengelly journal, Studies in Speleology, Volume 17. The photo shows Malcolm Cotter (in the green boiler suit) and me being interviewed and comes from the book Behind the Scenes at Time Team, by Tim Taylor (photos by Chris Bennett), published in 1998, which contains an extensive account of how the programme was made. Cooper's Hole can be seen in the background.

My renewed interest in the caves, and in particular a look at some of the exhibits in the museum, has reminded me about my unpublished notes - and in particular the need for lateral thinking in understanding how the caves formed. I therefore took the opportunity to make contacts to see if I can get some photographs taken of some important geological features - mainly relating to the shape of the roof of cave passages and chambers. There is no way, at 75, that I could safely re-enter the caves, and such pictures will help me to document my original notes in a scientifically usable form. The result could well be a couple of serious papers - plus further information which I could well publish on this blog.